NAIROBI, Kenya, Jul 24- On March 27, 2020, Kenyan authorities introduced measures to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, including a dusk-to-dawn curfew and a directive to Kenyans to work from home.

For “Wanjiku,” a 27-year-old pre-school teacher and single mother living in Mukuru Kwa Reuben, an informal settlement in Nairobi, that would be the start of the most difficult nine months of her life.

Her employer, a private school in Mukuru Kwa Reuben, immediately notified her and other staff that they would not be paid for as long as the school remained closed due to the pandemic.

When Human Rights Watch interviewed Wanjiku, who was with “Janet,” her four-year-old daughter, in November 2020 when schools were still under lock and key, they were struggling to make ends meet. It wasn’t until January 2021 that schools reopened.

Two days before the start of the lockdown, on March 25, President Uhuru Kenyatta announced a range of measures to cushion the economic impact of the pandemic, including adding Ksh10 billion ($100 million) to a social protection fund for the older people, orphans and those with underlying health conditions.

About two months later, the president announced a cash transfer program for the most socio-economically vulnerable populations, including people with disabilities, pointing out that his administration was already paying out Ksh250 million ($2.5 million) to the most vulnerable households each week.

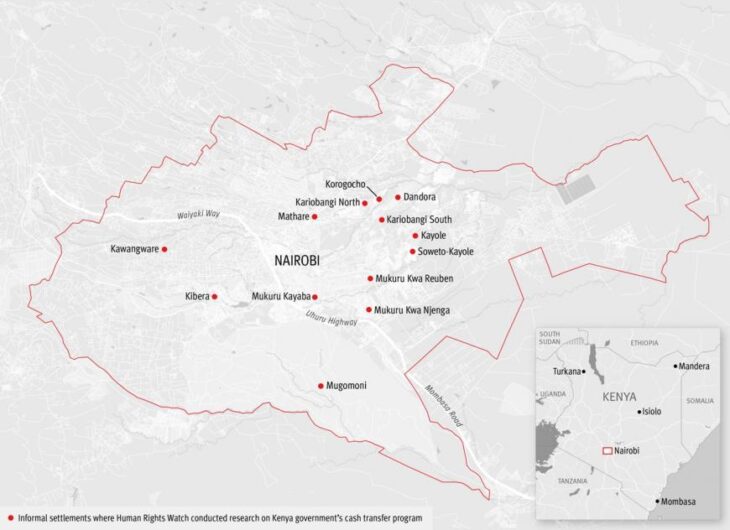

The research focused on Nairobi in part because it has the fastest growing number of informal settlements in the country and was one of the counties targeted by the government’s pandemic-related cash transfer program.

Of the 10 million people living in informal settlements across Kenya, 2.4 million live in Nairobi – making up half the city’s population yet crammed into only 1 percent of its land.

Residents of informal settlements, who are the most likely to live in extreme poverty and thus struggle to meet their basic needs, were also the most socio-economically affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Government-imposed public health measures intended to curb the spread of the virus, such as partial lockdowns and curfews, were more challenging to adhere to in informal settlements and had harsher economic consequences.

Government officials told Human Rights Watch that more than 60 percent of businesses in informal settlements were closed during the partial lockdown, exposing thousands of families to serious economic hardships.

High population density, lack of basic public services, poor electricity access, and pre-existing high rates of unemployment exacerbated the impact of these measure on residents.

Most employed residents work as unskilled laborers, earning around or below $1.90 (Ksh190) per day, an amount that leaves many unable to afford a minimum standard of nutrition and other necessities.

There is a gender dimension to poverty in Kenya According to government data, women are more likely to be unemployed, underemployed, underpaid, and seasonal workers. Females constitute 64.5 percent of the unemployed, 61.9 percent of all part time workers, and majority of the underemployed.

Kenya’s 2015/16 Integrated Household Survey results show that more than a third of households are headed by females, and that 30.2 percent of female headed households live below the poverty line compared to 26.0 percent of their male counterparts.

A survey conducted in May 2020 showed that the labor force participation rate in the seven days preceding the survey was higher for males (65.3 percent) while slightly more than half (51.2 percent) of the females were found to be outside the labor force in the reference period.

Human Rights Watch spoke with dozens of people living in Nairobi’s informal settlements who said that, since the lockdown-induced loss of jobs and economic crisis, they have faced extreme hunger, going entire days without meals, in some cases up to four days a week, and have accumulated rent arrears of up to nine months.

Several said landlords evicted tenants for nonpayment of rent while some men abandoned their families – spouses and children – in the city altogether and returned to their upcountry homes.

Also, most women in Kenya work part-time in the informal sector, including as domestic workers where they cannot render services remotely, thereby losing income, and in the service industry, where they are likely to have no job security and safety nets when crises such as Covid-19 hit the economy.

Despite President Kenyatta’s pledge to cushion the most economically and socially vulnerable from the impact of the government’s pandemic response, few households received the promised relief.

The cabinet secretary for Treasury and Planning, Ukur Yatani, told Human Rights Watch in January 2021 that the cash transfer program ran from April 22 to November 27, 2020 and, in its first phase, targeted 85,300 households in four counties: Nairobi, Mombasa, Kilifi and Kwale.

In its second phase, he said the program reached an additional household in 17 other counties.

He added that the authorities prioritized support for households in informal settlements with high poverty index; where the head or breadwinner has a physical disability; is widowed; is a minor (orphan or child-headed households); have pre-existing medical conditions such as cancer or HIV; has a mental health condition and are not benefiting from other government support.

The whole country remains, at time of writing, under a dusk-to-dawn curfew that began in March 2020 when the pandemic hit.

For 30 days in April 2021, travel to or from Nairobi, Kajiado, Machakos, Kiambu and Nakuru counties was also prohibited. Of the 85,000 households that benefitted from the cash transfers in the first phase, 29,000 were from informal settlements in Nairobi county – which amounts to less than 5 percent of the 600,000 households in Nairobi’s informal settlements.

Map Courtesy of HRW.

Moreover, this report found that the cash transfer program lacked clear rules and basic transparency and did not appear to recognize that everyone has a right to social security and an adequate standard of living, including food, leading many eligible people not to be registered and enabling corruption and favoritism in its implementation.

There is no mechanism for people like Wanjiku who missed out, to appeal or challenge the decision to leave them out. Authorities did not publish any information about the program’s start date and duration; eligibility criteria; or the amount and frequency of payments.

In addition, the national government’s devolution of implementation to multiple groups with little coordination or oversight compounded corruption risks.

Human Rights Watch interviews surfaced numerous allegations that officials in charge of enrolment frequently ignored government-approved eligibility criteria, which failed to ensure the assistance reached everyone at risk of hunger, and directed benefits to their relatives or friends, even in cases when they did not meet the criteria.

Many of the residents of informal settlements in Nairobi with whom Human Rights Watch spoke, who appeared to be eligible for the program, said they did not register for it because they were simply not aware of its existence.

Others, including those living in households headed by people with disabilities, have serious pre-existing medical conditions such as cancer or HIV/AIDS, and older people, said they registered but did not receive any benefits.

Several said they received some cash transfers between April and July, although the number of payments varied widely and some reported that they received the money for only one or two months.

Only a small fraction of beneficiaries said they received the cash for the entire authorized period that extended from April to November.

This report found that, in some areas, the authorities engaged Nyumba Kumi, or village elders who head clusters of 10 households, to oversee the program’s implementation, while in other areas it fell to community health volunteers or resident savings associations. Interviewees charged with enrollment told Human Rights Watch that they had not been trained or given any selection criteria or guidelines and they therefore selected people they knew.

Some beneficiaries said they were enrolled by local politicians, who were either given free reign by authorities to select a certain number of people or who were given control over enrolment delegated to others.

The report found that the involvement of politicians made the process more vulnerable to cronyism than when implemented by Nyumba Kumi cluster leaders or Community Health Volunteers.

At least six residents of informal settlements alleged that members of parliament and Nairobi county assembly used their allocated benefits for friends and family members, even in cases when they were not eligible.

In Mukuru Kwa Reuben, a 29-year-old father of two who benefited from the cash transfers after he was enrolled/registered by a Nairobi politician told Human Rights Watch that he has a stable job with a decent salary and wasn’t really in serious need.

Even for those lucky enough to be enrolled, not all ultimately received the cash. Government officials told Human Rights Watch that about half of those enrolled received the money, and not throughout the authorized duration.

It is unclear who and how the decision was made to drop some of the enrolled names. Human Rights Watch calls on Kenyan authorities to make a comprehensive list of all households that received cash transfers available to the auditors and any other government agencies monitoring the program.

The frequency of the transfers also varied. Contrary to the government’s claim that each beneficiary received a total of 35 transfers in eight months, most of those who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they received the transfers just twice or four times in that period. While some beneficiaries received the cash weekly, many received money every two weeks and others once a month.

Like for many countries, the challenges Kenyan officials face in the midst of a health crisis to effectively provide support to families on the brink of hunger exposes the huge gaps in the country’s existing social protection system.

There is no recognition of the right of everyone to social security nor any attempts to create a comprehensive system of social security.

The efforts to expand coverage, and the lessons learned, present a critical opportunity to develop social protection programs based on the right of everyone to social security and to an adequate standard of living.

According to the World Bank, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic will push an additional 88 million to 115 million people into extreme poverty worldwide, bringing the total to between 703 and 729 million.

The “new poor” is forecasted to be more urban than those who have persisted in poverty for a longer time; more engaged in informal services; live in congested urban settings; and work in the sectors most affected by lockdowns.

Kenya, as a state party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is obligated under article 11 to ensure that Kenyans enjoy the right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate housing as well as the fundamental right to adequate food and freedom from hunger and malnutrition.

There are similar protections under article 25 (1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

In General Comment 12, the ICESCR Committee, which monitors implementation of the International Covenant on economic, social and cultural rights by its States parties, said that whenever an individual or group is unable, for reasons beyond their control including natural or other disasters, to enjoy the right to adequate food by the means at their disposal, governments have the obligation to provide that right directly.

ICESCR and other human rights law also require Kenya to respect and implement the right of everyone to social security.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which interprets the African Charter and considers individual complaints, has interpreted the right to social security as implicit from a joint reading of several rights guaranteed under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights including the rights to life, dignity, liberty, work, health, food, protection of the family and the right to the protection of the aged and the disabled.

Kenya is a state party to the African Charter and has included these rights in its national constitution.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Kenyan government to take urgent steps to fulfil its obligation to ensure that residents of informal settlements can meet their basic needs to adequate food and housing.

The authorities should investigate the implementation of the cash transfer program and hold those credibly implicated in any misuse or misappropriation of funds should be held to account.

The government should guarantee that social assistance programs respect the principles of equality and nondiscrimination.

The article was first published by the Human Rights Watch on their website.

Want to send us a story? Contact Shahidi News Tel: +254115512797 (Mobile & WhatsApp)