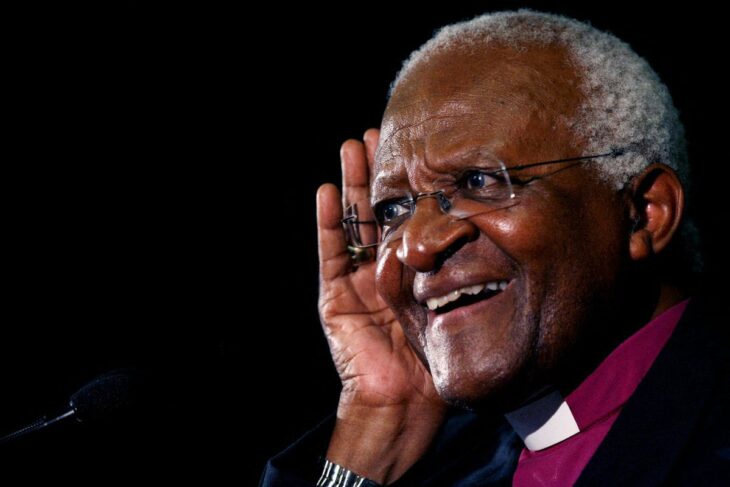

Dec 26, (Reuters) – “Like falling in love” is how Archbishop Desmond Tutu described voting in South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994, a remark that captured both his puckish humour and his profound emotions after decades fighting apartheid.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu, the Nobel Peace laureate whose moral might permeated South African society during apartheid’s darkest hours and into the unchartered territory of new democracy, died on Sunday. He was 90.

The outspoken Tutu was considered the nation’s conscience by both Black and white, an enduring testament to his faith and spirit of reconciliation in a divided nation.

He preached against the tyranny of white minority and even after its end, he never wavered in his fight for a fairer South Africa, calling the black political elite to account with as much feistiness as he had the white Afrikaners.

In his final years, he regretted that his dream of a “Rainbow Nation” had not yet come true.

On the global stage, the human rights activist spoke out across a range of topics, from Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories to gay rights, climate change and assisted death – issues that cemented Tutu’s broad appeal.

“The passing of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” said President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Just five feet five inches (1.68 metres) tall and with an infectious giggle, Tutu was a moral giant who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his non-violent struggle against apartheid.

He used his high-profile role in the Anglican Church to highlight the plight of black South Africans.

Asked on his retirement as Archbishop of Cape Town in 1996 if he had any regrets, Tutu said: “The struggle tended to make one abrasive and more than a touch self-righteous. I hope that people will forgive me any hurts I may have caused them.”

Talking and travelling tirelessly throughout the 1980s, Tutu became the face of the anti-apartheid movement abroad while many of the leaders of the rebel African National Congress (ANC), such as Nelson Mandela, were behind bars.

“Our land is burning and bleeding and so I call on the international community to apply punitive sanctions against this government,” he said in 1986.

Even as governments ignored the call, he helped rouse grassroots campaigns around the world that fought for an end to apartheid through economic and cultural boycotts.

Former hardline white president P.W. Botha asked Tutu in a letter in March 1988 whether he was working for the kingdom of God or for the kingdom promised by the then-outlawed and now ruling ANC.

Among his most painful tasks was delivering graveside orations for Black people who had died violently during the struggle against white domination.

“We are tired of coming to funerals, of making speeches week after week. It is time to stop the waste of human lives,” he once said.

Tutu said his stance on apartheid was moral rather than political.

“”It’s easier to be a Christian in South Africa than anywhere else, because the moral issues are so clear in this country,” he once told Reuters.

In February 1990, Tutu led Nelson Mandela on to a balcony at Cape Town’s City Hall overlooking a square where the ANC talisman made his first public address after 27 years in prison.

He was at Mandela’s side four years later when he was sworn in as the country’s first black president.

“Sometimes strident, often tender, never afraid and seldom without humour, Desmond Tutu’s voice will always be the voice of the voiceless,” is how Mandela, who died in December 2013, described his friend.

While Mandela introduced South Africa to democracy, Tutu headed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that laid bare the terrible truths of the war against white rule.

Some of the heartrending testimony moved him publicly to tears.

But Tutu was as tough on the new democracy as he was on South Africa’s apartheid rulers.

He castigated the new ruling elite for boarding the “gravy train” of privilege and chided Mandela for his long public affair with Graca Machel, whom he eventually married.

In his Truth Commission report, Tutu refused to treat the excesses of the ANC in the fight against white rule any more gently than those of the apartheid government.

Even in his twilight years, he never stopped speaking his mind, condemning President Jacob Zuma over allegations of corruption surrounding a $23 million security upgrade to his home.

In 2014, he admitted he did not vote for the ANC, citing moral grounds.

“As an old man, I am sad because I had hoped that my last days would be days of rejoicing, days of praising and commending the younger people doing the things that we hoped so very much would be the case,” Tutu told Reuters in June 2014.

In December 2003, he rebuked his government for its support for Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, despite growing criticism over his human rights record.

Tutu drew a parallel between Zimbabwe’s isolation and South Africa’s battle against apartheid.

“We appealed for the world to intervene and interfere in South Africa’s internal affairs. We could not have defeated apartheid on our own,” Tutu said. “What is sauce for the goose must be sauce for the gander too.”

He also criticised South African President Thabo Mbeki for his public questioning of the link between HIV and AIDS, saying Mbeki’s international profile had been tarnished.

A schoolteacher’s son, Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, a conservative town west of Johannesburg, on Oct. 7, 1931.

The family moved to Sophiatown in Johannesburg, one of the commercial capital’s few mixed-race areas, subsequently demolished under apartheid laws to make way for the white suburb of Triomf – “Triumph in Afrikaans.

Always a passionate student, Tutu first worked as a teacher. But he said he had become infuriated with the system of educating Blacks, once described by a South African prime minister as aimed at preparing them for their role in society as servants.

Tutu quit teaching in 1957 and decided to join the church, studying first at St. Peter’s Theological College in Johannesburg. He was ordained a priest in 1961 and continued his education at King’s College in London.

After four years abroad, he returned to South Africa, where his sharp intellect and charismatic preaching saw him rise through lecturing posts to become Anglican Dean of Johannesburg in 1975, which was when his activism started taking shape.

“I realised that I had been given a platform that was not readily available to many Blacks, and most of our leaders were either now in chains or in exile. And I said: ‘Well, I’m going to use this to seek to try to articulate our aspirations and the anguishes of our people’,” he told a reporter in 2004.

By now too prominent and globally respected to be thrust aside by the apartheid government, Tutu used his appointment as Secretary-General of the South African Council of Churches in 1978 to call for sanctions against his country.

He was named the first Black Archbishop of Cape Town in 1986, becoming the head of the Anglican Church, South Africa’s fourth largest. He would retain that position until 1996.

In retirement he battled prostate cancer and largely withdrew from public life. In one of his last public appearances, he hosted Britain’s Prince Harry, his wife Meghan and their four-month-old son Archie at his charitable foundation in Cape Town in September 2019, calling them a “genuinely caring” couple.

Tutu married Leah in 1955. They had four children and several grandchildren, and homes in Cape Town and Soweto township near Johannesburg.

Want to send us a story? Contact Shahidi News Tel: +254115512797 (Mobile & WhatsApp)