GARISSA, Kenya, May 30- A cloud of uncertainty hovers around Dadaab and Kakuma camps, homes to thousands of refugees, following a decision by the government to close them.

The Government on March 24 issued a 2 week notice for to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, to devise a road map for the “definite” closure of the two camps.

It is not first the time Kenya has threatened to close the camps, over claims they have become a breeding and recruiting grounds for terrorism.

The reports of an imminent closure were received in shock by the refugees, most of whom have been born and raised at the camp.

“As a refugee born and raised in the camps, some of us have lived and known only the camps and raised kids here. We don’t have else where to go,” a Somali refugee told Shahidi News.

“Since when the order was released, we are heartbroken and we don’t get enough sleep, thinking the next move by the Government of Kenya.”

Such is the story of Abdullahi Osman, a Somali refugee who was born and raised at the Dadaab refugee complex.

Their parents came here 31 years ago at the height of the civil war in Somalia, after the fall of President Siad Barre.

“Going back to Somalia is not an option,” he said of his country, currently embroiled in political uncertainty and constantly facing the threat of terrorism.

And though some relative calm has been witnessed and more so in some parts of Mogadishu, the capital city, the ugly face of terror, keeps on rearing its ugly head.

“At this time, there is no ready land and peaceful place to return in Somalia,” Osman said.

While at the camp, he has been following on the recent political activities and he fears, if well not handled, it will only worsen and already dire situation.

“There is a political conflict between Somalia Federal governments and Federal State and taking our kids to such chaos will be disastrously.”

When Dahabo Ahmed came to Kenya, she was a mother of two kids and was young and energetic. She now has 10 children.

At 61 years, she wonders, “where will I go to?”

“I don’t know where to move to. I don’t have a country and people to run to. I am thankful to Kenya for giving us peace, shelter and land to settle. But where will I go?”

She is calling on the government to consider their plight, before taking any drastic action, a similar appeal like one made by UNHCR.

“I appeal to the Government of Kenya to halt the plans to close the camps. Because of this order we are feeling mentally and emotionally burnt out,” a teary Ahmed said during an interview with Shahidi News.

“There is nowhere to take my kids, where should I take them, what should I do with them? I don’t know where to go?” she asked.

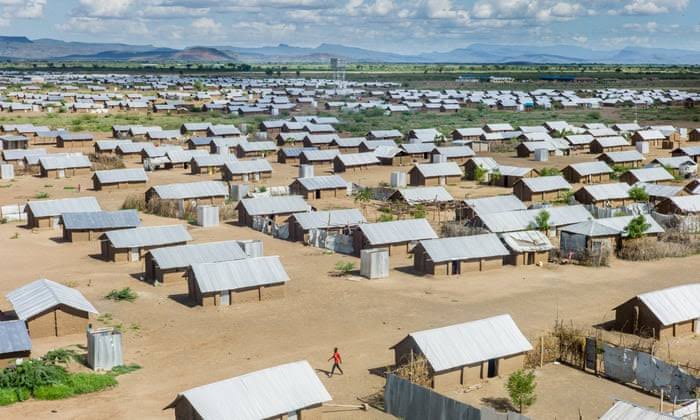

Dadaab refugee complex consists of three camps. The first camp was established in 1991, when refugees fleeing the civil war in Somalia started to cross the border into Kenya.

A second large influx occurred in 2011, when some 130,000 refugees arrived, fleeing drought and famine in Southern Somalia.

In 2018, the Ifor camp was closed down when most of its residents were repatriated back home with help from UNHCR.

Over the last few years, Somalia has been hit by a dessert locust invasion, floods that have left farmlands barren, severe weather conditions and a security threat, that has threatened not just their homeland, but neighbouring Kenya as well.

For Osman, “we are better here in Kenya than Somalia. There is no education or good health in Somalia. We would want to return to our country at the right time when the country is stable.”

UNCHR has since called on the government to reconsider its decision, saying it has a potential of negatively impacting on the lives of refugees including compromising their safety amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We are not against repatriation and we would love to go back to our country but it’s not possible for us to move out in 14 days or even 3 months. We ask the Government of Kenya to follow a repatriation process while respecting our rights as refugees,” Farah Farah, another refugee from Somalia said.

Their sentiments are echoed by refugees at Kakuma camp.

“We are happy here at least we have peace and are assured of a meal,” Deah Africk, an Ethiopian refugee said.

For Ahmed Farah, a Kenyan living at Kakuma, the government should instead register the refugees as citizens.

“We have lived with these people for more than 30 years. We have married their daughters and some have married our daughters. We are one,” he said.

Tens of refugees who spoke to Shahidi News, some from South Sudan like Susan Auche, feel Kenya is more home to them than their countries of origin.

“I live and feel like a Kenyan. I should be allowed to live here,” she said.

Others interviewed were from Burundi and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The Dadaab refugee complex which consists of three camps: Dagahaley, Ifo and Hagadera, was established in 1991 when refugees fleeing the civil war in Somalia started to cross the border to Kenya.

According to UNHCR as of July 2020, the complex was a host to 218,873 registered refugees.

The Kakuma refugee camp consisting of the Kakuma camp and the Kalobeyei integrated settlement is a host to 196,666 refugees and asylum seekers according to statistics from the UNHCR as of July 2020.

Kenya argues that the camps have become a threat to their very own existence.

According to intelligence reports, the 2 camps have been used as breeding and recruitment ground for terrorists who have gone on to wage attacks across the country including the Westgate Mall attack in 2013, that claimed 67 lives.

Other major attacks said to have been planned in the camps include the 2014 attack in Mpeketoni that saw more than 60 people killed and the Garissa University College attack in 2015 where 148 mostly innocent students’ lives were claimed.

At one point, the Dadaab refugee complex was the biggest in the world before a November 2013 Tripartite Agreement was signed by the Government of Kenya, the Federal Government of Somalia and UNHCR, to provide a framework for the voluntary return of Somali refugees from the country.

Though thousands were repatriated, the process and timelines set by the Kenyan government were not properly executed due to several hitches.

With this, Kenya accused the International Community of not playing its part for failing to consistently contribute to a kitty designated and agreed upon by parties to ease the repatriation process.

Want to send us a story? Contact Shahidi News Tel: +254115512797 (Mobile & WhatsApp)